I Got My wOBA Tangled in My rOBA and Tripped on My FIP

A old-timer's look at how advanced statistical models compare to the stats on the back of a baseball card.

This article originally appeared in Here’s the Pitch, the newsletter of the Internet Baseball Writers Association of America.

If you are a baseball fan of a certain age, you probably learned most of what you know about baseball statistics like I did – from the backs of baseball cards. It was a simpler time. You rated your heroes by BA and ERA and H and HR and W and L and SO and BB and you were happy. Today things are much more complicated. Bill James and Moneyball and Sabermetrics happened and now all the data available can’t fit on a multi-page spreadsheet, let alone the back of a baseball card. All this data can be daunting to a baseball writer raised on AB and PO.

Don’t get me wrong, I am no Luddite seeking to overthrow the wheels of progress. The new statistics have greatly increased both my enjoyment and understanding of the game. It has also helped elevate the value of previously undervalued players like a Brett Gardner or Carlos Ruiz. It forces a reckoning on what really constitutes a great player and enriches arguments about who does and does not belong in the Hall of Fame. It is just that this sea of data can be the cause of vertigo for the baseball writer who grew up thinking RBI was a key statistic. How do I square my instinct to look at batting averages and earned run averages to evaluate players with the new math that tells me to look deeper?

To deal with my confusion, I decided to look at the statistics for a comparable set of hitters and a comparable set of pitchers. I chose players who were retired and from two different eras – the 1950s and the 1990s. The older player is in the Hall of Fame, the younger is not. I also chose players I had seen play for an extended period, because I still trust my eyes more than my BAbip. Here is what my comparison showed. Who among these belong in the Hall?

For the hitters I chose two long time center fielders and lead-off hitters, Richie Ashburn and Kenny Lofton. Here is the comparison using traditional statistics.

As you can see these two players had similar career lengths in terms of years, games, at bats and hits. Ashburn hit for a slightly higher average and Lofton hit with considerably more power. Ashburn’s on-base percentage, a traditional measure for lead-off hitters, is .396, a good bit higher than Lofton’s .372. On the other hand, Lofton was a much more prolific base-stealer, influenced in part by the premium put on stolen bases in his era.

Now let’s look at player value using more advanced metrics.

These figures result in some mixed messages. Rbat (Runs batting) and Rrep (Runs above replacement) would indicate a clear superiority in runs produced for Ashburn. On the other hand, Lofton has a clear advantage in dWAR (defensive Wins Above Replacement) a critical statistic for a position like center filed. While these data would indicate Lofton was the superior fielder, traditionalists might point out that six of the all-time top ten seasons for putouts by an outfielder were recorded by Ashburn. The salary line shows one clear difference in the two eras that we all can understand.

Finally for these two players, what can these “Advanced” metrics tell us.

Here we see the players with nearly identical BAbip (Batting Average of balls in play) at .327 and .326 respectively. Ashburn, a prolific walker, has the advantage in OPS+, while Lofton blows Ashburn away on PwrSpd (combined Power and Speed).

Taking all the data together, I would conclude that these are two comparable players who fall in the marginal Hall of Famer category. The advanced metrics help Lofton’s case for induction, but I am not sure that the case is not also made by the standard measures from the back of his baseball card.

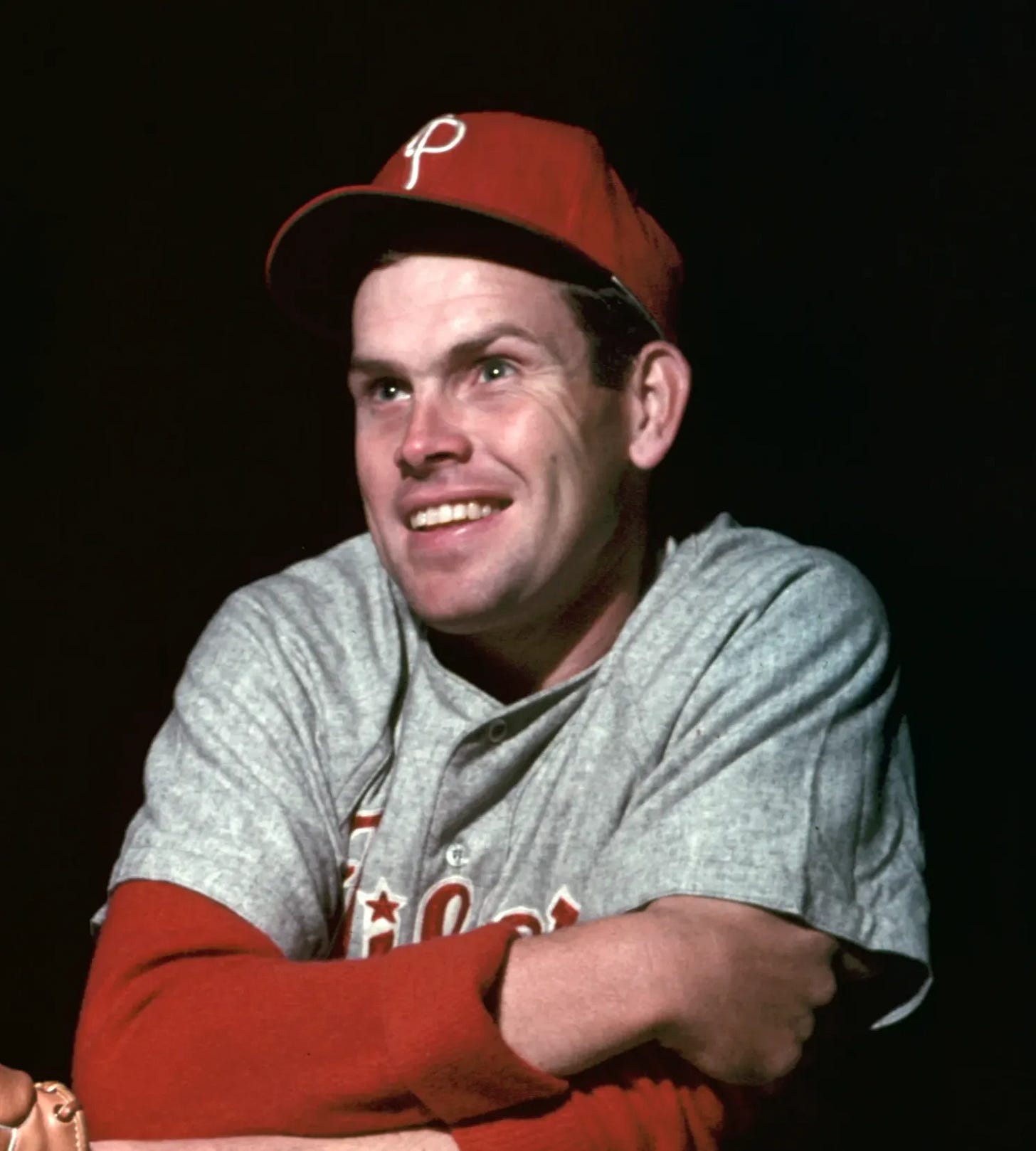

Now let’s look at pitchers Robin Roberts and Curt Schilling. Both were right-handed power pitchers and workhorses for their teams. Schilling compiled a remarkable post-season record pitching with the Red Sox and Diamondbacks, while Roberts won 20 or more games six seasons in a row, mostly with a mediocre team.

Standard measures show that Roberts won and lost many more games than Schilling. Schilling had a much higher W-L %, while Roberts, pitching in the 1950s before relievers took on the larger role they have today, blows Schilling away in terms of CG (complete games). ERA and WHIP (Walks + Hits per Innings Pitched) are close, while Schilling was the greater strikeout pitcher.

In doing my research for various articles I have written I have found ERA+ to be useful construct. ERA+ attempts to normalize earned run average for ballpark effects. Schilling scores somewhat higher on ERA+ at 127 to 113. FIP (Fielding Independent ERA) is also useful because it uses the same numerical construct as ERA but tries to determine what a pitcher’s ERA would be independent of a good or poor defense behind him. Again, Schilling (3.23) shows up a bit better than Roberts (3.51).

What about the value metrics?

Roberts comes out higher in WAR (Wins Above Replacement), while Schilling has a considerably higher WAA (Wins Above Average). Statisticians looking into the qualifications for entry into the Hall of Fame find the WAA statistic to be more useful. WAA compares a player to the average major league player, while WAR compares a player to a replacement level (i.e. minor league) player. There is no question that Roberts belongs in the Hall, but advanced metrics would indicate that Schilling, who came close last year, certainly belongs in there, too.

Thank you for joining me in my journey to integrate advanced metrics into my “back-of-the-baseball-card” mentality. My nostalgia for the well-placed bunt or the complete game may sometimes cloud my vision. A better grasp of the advanced metrics of the 21st century will help us all make more clear-eyed assessments.

Nice work here Russ. I don't know that it's an old-timer's look since it seems very sane to me to compare what we used to what we do now. Ashburn and Lofton are both marginal HOFers as you point out no matter how you parse!

Schilling would already be in if not for his personality.