Complete Games Make Baseball More Fun

This story of a game from 75 years ago illustrates how times have changed in baseball; not necessarily for the better.

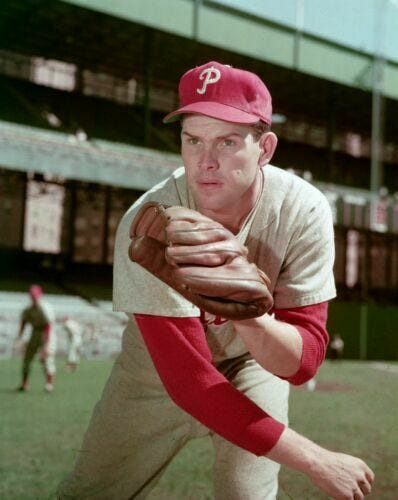

I love complete games. This is due, at least in part, to the time I grew up – the 1950s and 1960s, when pitchers were expected to finish what they started. My two favorite pitchers in those years were the Phillies Robin Roberts and the Braves Warren Spahn. Unsurprisingly, these two were the two leading complete games pitchers of their era. Spahn tossed 382 complete games in his career and Roberts 305, including 28 in a row in 1952-53.

The complete game is pretty much a lost art in baseball. Roberts threw 33 complete games in 1953. In 2024, the entire starting pitching contingent of both leagues threw a grand total of 28. The game has changed, and I am sure the analytics show that you improve your chances of winning if you use a starter for 5 or 6 innings and then finish with three or four relievers. Still, I miss the complete game. The one I describe below is both illustrative of the charm of the complete game and the way Major League Baseball has changed in 75 years.

On June 5, 1950, the Philadelphia Phillies were taking on the St. Louis Cardinals at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis. The two teams both had pennant ambitions and were currently in a virtual three-way tie for first place with the Brooklyn Dodgers. The Phillies were pitching their young ace, 23-year-old Robin Roberts. The Cardinals countered with three-time All Star, veteran Red Munger. Neither pitcher would have their best game of the year, but one of them was still standing at the end.

After an uneventful first inning, slugger Del Ennis broke the ice for the Phillies with a leadoff home run in the top of the second. In the bottom of the second, Roberts worked around a walk to left fielder Bill Howerton, a shortstop Eddie Miller single, and an Ennis error in right field, to escape with no runs allowed. The third inning was scoreless, although Roberts was in trouble again after walking the pitcher Munger and hitting Stan Musial with a pitch. The wildness was uncharacteristic of Roberts, who finished his career as one of the premiere control pitchers of his era.

A double play groundball got Munger out of the fourth inning easily enough, but Roberts was in trouble again in the bottom of the fourth. He again walked Howerton, the leadoff batter in the inning. Former Phillie Harry “The Hat” Walker followed with a single, Howerton stopping at second. Roberts then bobbled Miller’s bunt for an error loading the bases. At this point, Roberts, who famously always held something in reserve on his fastball, struck out catcher Del Rice, Munger, and third baseman Tommy Glaviano in succession to escape the inning.

The Phillies extended their lead in the fifth inning, when catcher Andy Seminick tripled and Roberts singled him home. Roberts could not escape trouble in the bottom of the inning, however. Musial doubled with one out and then, after Roberts got the second out, Howerton lifted a long fly ball to left that Dick Sisler got his glove on, but could not hold. It was ruled a double. Musial scored the Card’s first run. Walker scored Howerton with a single and the game was tied, 2-2. Eddie Miller also singled, but Roberts retired pinch hitter Eddie Kazak on a foul pop-fly to end the inning.

Each team had runners on base in the sixth and seventh, but no one scored. In the eighth, the Phillies took the lead on back-to-back doubles by shortstop Granny Hamner and first baseman Eddie Waitkus. Roberts set the Cardinals down in order, including a strikeout, his seventh of the game, of pinch hitter Johnny Lindell, batting for pitcher Munger.

Al Brazle replaced Munger on the mound for the ninth and what had been a tight pitcher’s duel turned into an offensive explosion. Brazle got the first two outs, but the Phillies then banged out four consecutive singles, with Ennis’ single scoring three runs when left fielder Howerton allowed the ball to roll through his legs. The Phillies led 7-2.

Roberts strode to the mound for the ninth. Up to this point he had given up eight hits, walked three, hit a batter, and compiled seven strikeouts. While pitch counts were not recorded in these days, he was surely closing in on 120 pitches. Many of those pitches, in a close game with lots of runners on base, were high stress pitches as well,. Jim Konstanty, the best relief pitcher in baseball in 1950, was in the bullpen. In today’s game, Roberts would not have been sent out to pitch the ninth, but this was a different time.

The Redbirds opened the ninth with three consecutive singles by Red Schoendienst, Musial, and Enos Slaughter. Phillies manager Eddie Sawyer went to the mound. Philadelphia Inquirer sportswriter, Stan Baumgartner observed that Roberts was “visibly tired.” After a brief discussion with his pitcher, however, Sawyer returned to the dugout. Howerton, who had been a thorn in Roberts’ side all game, singled scoring Schoendienst and Musial. Luckily for Roberts and the Phillies, Slaughter was thrown out at third base on a nifty relay from centerfielder Dick Whitman to Hamner to third baseman Willie Jones. Howerton moved to second on the throw.

The dangerous Walker then popped out to Jimmy Bloodworth at second for the second out of the inning, but Miller singled home Howerton and the score was now 6-5. Sawyer again strode to the mound. This was before the days when two visits to the mound in an inning meant you had to remove the pitcher. Again, Sawyer conferred with the tiring Roberts. Again, he strode back to the dugout deciding to leave his pitcher in the game. Roberts drew on all his reserves and got backup catcher Johnny Bucha to bounce to Hamner for a force out to end the game.

It was Roberts seventh win of the season, against two losses. Both losses had come to the Cardinals, so this was a sort of payback. Roberts final pitching line showed 9 innings pitched, 13 hits, 3 earned runs, 3 walks, 7 strikeouts, a hit batter, and 44 batters faced. If he threw an average of 3.5 pitches per batter, a conservative estimate, he threw 154 pitches. Roberts took the ball four days later for his start against the Pirates, lasting six innings before giving way to Konstanty. He threw 304 innings that year with 21 complete games.

I am not sure if Eddie Sawyer was practicing smart baseball, but I do know he was practicing entertaining baseball. There is nothing quite like watching a great pitcher gut it out to finish what he started, even if he was not at his best in the end.

Today if a pitcher has one or two complete games, it’s a big deal. They don’t make them like they use to.

Nice reminiscent story Russ! Roberts best baseball buddy Curt Simmons had a great description of Roberts; “he was like a diesel engine, start him up and he’d go all day.” Sawyer was once asked about letting Roberts pitch so much and he had an interesting answer. “Except for 1950 and Konstanty, when I looked out to the bull pen there was no one better than Robbie so I just let him pitch out of it.”